This guest post was written by Emma Higgs and is part of her Faith in the Fog series about her experiences with doubt, skepticism, mental health, and forging a different kind of faith. You can follow the entire series on her blog.

There are certain ways Christians talk about God that turn me into an atheist.

I can’t help it. As much as I try to ignore it, my inner skeptic is constantly on the lookout for holes in the God theory. It will find a loose thread and keep tugging until the whole thing unravels. Before I know it, my cherished beliefs in a loving God have disintegrated and I’ve unwittingly written off the entire Christian faith as superstitious nonsense.

Any troubling question or rogue thought can trigger this unravelling process. But few things give my inner skeptic a firmer foothold than Christians making statements of apparent certainty regarding their beliefs.

We are certain that God will prevent this bad thing from happening.

This is definitely what will happen when we die.

This is the one correct interpretation of this two-and-a-half-thousand-year-old passage of Hebrew scripture.

Really?

Sometimes I feel like being a Christian requires me to switch off my brain altogether.

Now, this confidence and assuredness seems to work for a lot of people. But for me, an assertion like that is all it takes for the fog to descend. Questions and doubts start spinning around my overzealous monkey brain, rapidly eroding any hope I had that this Christianity thing might be true.

You see, I was brought up to believe that Christianity was mainly about believing in certain doctrines. The main function of the church seemed to be to help me understand these doctrines, and to convince me of just how correct they were. If I was ever to lose my faith in said doctrines, well, let’s just say my fire insurance policy would be null and void.

The lingering effect of this particular introduction to Christianity is that I still have an underlying, often subconscious assumption that correct beliefs are the point of it all. So when doubt sets in and my beliefs begin to evaporate before my eyes, it’s no surprise that my gut response is usually to panic.

A different kind of knowing

I strongly suspect that whenever any of us get too caught up in the specifics of belief — whether we are confidently asserting faith in a particular doctrine or being thrown into blind panic by our doubt — we are missing the point.

The thing about a subject like God is that it is, by definition, beyond our understanding. So when we use language to describe God, our words are never going to accurately represent the reality we are describing.

The writers of the Bible use metaphors, symbolism, and poetic language to describe their experiences of God, simply because this is the closest we humans can get to conveying a reality so far beyond ourselves. These poems and metaphors can be true in the deepest sense without being scientifically provable.

We Christians tend to cling to our beliefs because they provide a reassuring framework in which everything is categorized and understood. But in doing so we risk losing the very heart of Jesus himself, who insisted upon disrupting our ideological constructs, defying our expectations, and merging our categories.

This does not sit well with us. We modern, post-enlightenment folk like to have control, to have things neatly encapsulated within our understanding. If something is true, surely we must be able to nail it down and explain how it works. We like to think we can know about God in the same way we can know about the mechanics of a car or the anatomy of an insect. But seeking objective knowledge about God is like chasing the wind. A subject like God requires a different kind of knowing.

So when the questions start to whirl and the and the panic of unwilling atheism sets in (which it does on a fairly regular basis), I have to remind myself that my beliefs about God are not the foundation of my faith.

I will not find God by thinking harder, by using the power of reason to convince myself intellectually that a particular set of beliefs are true.

But if I instead focus my energy on walking in the way of Jesus — loving my neighbor, practicing forgiveness, standing against injustice, and speaking out for those who have no voice — I wonder if I might just find myself staring God in the face.

Uncertainty is uncomfortable. I would love to have all the answers. But I think that would make me God, and I suspect I don’t have the qualifications.

Expanding our God vocabulary

I wonder if the church might have an easier time relating to people today if it was willing to think creatively and expand its vocabulary of God metaphors.

I think one of our biggest problems is that we are still a bit stuck with the idea of God being up there, occasionally intervening down here. Like some sort of cosmic super-genie, granting wishes from above. But the whole point of the Jesus story is that God is with us. The curtain in the temple was torn in two, and there is no longer any separation. God is not looking down on us, demanding appeasement and hurling blessings and curses from on high — that’s what every other god in the ancient world did. According to the New Testament, this God is in the sweat, blood, and dirt of our lives, with us in our weakness and in some mind-boggling way, suffering alongside us.

If my doubt and confusion feel like a fog, then God is in that fog, not hidden behind it.

When I’m losing faith in a particular statement or belief about God, it helps me to remember that there are many other God metaphors I can turn to if the more traditional ones lose their appeal.

I can choose to think of God as Source, breath, ultimate reality, Ground of Being…

The energy and luminescence behind all of life…

The Divine Mother who nourishes us within her womb…

The unquenchable spark of humanity…

The light that pierces the darkness…

The ocean that surrounds us, saturating all things…

The unspeakable beauty woven into the very fabric of the universe.

These ideas are deliberately vague; they aren’t meant to stand up to scientific scrutiny. Some things can only be described poetically, because to try and literalize them would reduce their meaning. As with all language attempting to describe the indescribable, they are abstract words, none of which contain God, so I hold them with a loose grip. But with a wide repertoire of God metaphors at hand, it’s easier to prevent my inner skeptic from denying God’s existence altogether

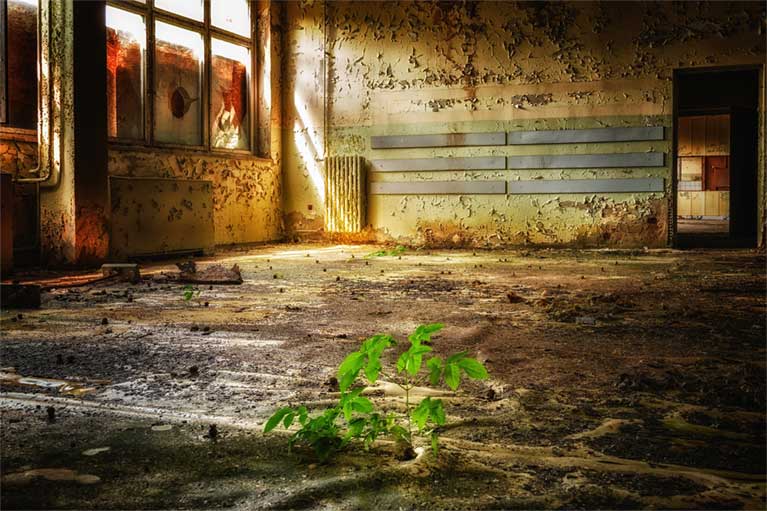

In letting go of concrete beliefs as the foundation of my faith, I dare to hope that I am more open to experiencing the reality of the presence of God in this moment. God in the soil, in the breeze, in laughter, in the faces of strangers I would usually avoid, and in the last places on earth I would think to look.

Without my own fixed ideas and constructs limiting my perception, my eyes can be opened to the mystery of the divine, loving presence that infuses everything, pulsing through my veins and filling the air I breath.

“The God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands…

…For in him we live and move and have our being.” — Acts 17:24,28

Photo via Pixabay.

About Emma Higgs

About Emma Higgs

Emma Higgs is a musician, mum and lifelong church-goer living in Plymouth, England. She blogs about progressive theology and mental health, amongst other things, at www.emmahiggs.com. Find her on Facebook and Twitter.