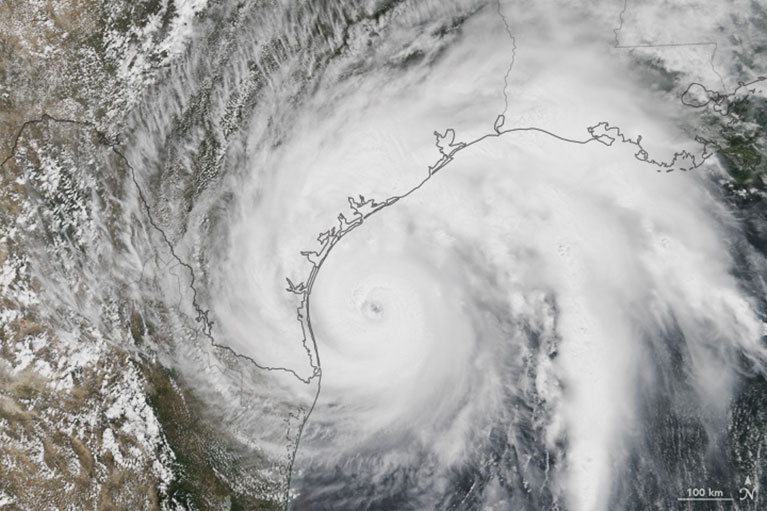

Hurricane Harvey approaches the coast of Texas, August 25, 2017, via NASA.

I turned the knob slowly, believing that anything I could do to preserve a few more minutes of silence would be worth it. Hannah, who falls asleep more slowly, was the first to respond. “Is it time?” she said. “Yes, it’s time again. Get up little girl.”

I walked over to her brother’s bed. “Aaron, c’mon. It’s time.” He rolled over, groggy. “Grab your things and put on your shoes.”

Growing up, it seemed that there were two types of people in the world: those that wore shoes in the house and those that didn’t. Neat people left shoes by the door, fastidious about white carpets and shiney linoleum. People less concerned about cleanliness and those with wood floors left shoes on, mostly.

But there’s something more to it than that, right? “Kick your shoes off and sit a spell” is what the old folks say. Even those who had dirt floors. Shoes-off in the house is about more than cleanliness. It’s about ease. Shoes-off in the house is about more than just safety. It’s about Sabbath. It’s about cessation of work, cessation of anxiety. Shoes-off is how we want to live, at least in a metaphorical sense.

If things really got bad there would be room for four in the closet. This was still just the tornado warning. First would come the breaking glass, then the freight train, then ducking inside and shutting the door and holding on for our lives. For the moment, Erica and I sat in the hallway, kids uneasily dozing in the closet-cum-storm-shelter, everyone with their shoes on, waiting for the storm. This is how the Callahams spent three long days at the end of last month; never leaving the house, but running from a storm nonetheless.

This was was also the scene that came pouring back to me when the Passover Ordinance, the story of Hebrew slaves ordered by God to eat with shoes on as they prepared to leave Egypt, appeared in the Sunday lectionary.

I don’t mean to equate the trials that Houston faced during hurricane Harvey with those of the Hebrews long ago. Contemporary urbanism is as far from Iron Age slavery as the weather patterns of Houston are from those of North Africa. Neither do I wish to compare the inconveniences that my family experienced with the horror of those who were literally out in the storm. Our stories are not the same, except for the shoes.

I wonder how the Hebrews felt as they cleaned up their final meal in Goshen? There must have been quiet moments to wonder about whether all the preparation had been worth it, to wonder whether the blood on the doorpost would actually work, to wonder whether the morning would bring another hardening of the heart of Pharaoh, a return to work and death. Did Hebrew children dose uneasily under their parents’ anxious gaze? Did anyone take comfort in the discomfort of dining with shoes on? Does the fear I felt while sheltering-in-place have anything to do with the hope that we are taught is at the heart of the Passover story?

In recent days, the inevitable question that accompanies most natural disasters has been raised. “Where was God in the midst of our storm?” Predictably, the voices that have risen to the top of the media are not those most prepared to answer. Rather, celebrities and pundits suggest one of two troubling things.

Principally and tragically, some suggest that God was the cause of the storm. That, like some eleventh plague, God was seeking to again turn hardened hearts by afflicting the masses. This is wrong. It shows neither understanding of the basic biblical narrative nor nuance in its interpretation. The citizens of Houston were not waiting for salvation, not of this type at least. Moreover, God has shown that the wanton destruction of life and property is no longer his game, even if it ever was.

More pleasant, but similarly challenging, is the suggestion that God was present in the hands and feet of the heroic rescuer who, like a contemporary Moses, parted water in boat or truck to free those trapped by rising water. This is closer to the truth. But, it still disenfranchises those who cowered in closets, shivered on rooftops and waited for phone calls from lost loved ones. Yes, we owe much to our rescuers and their bass boats. But was God not also present in the lives of the others as well?

The same lectionary’s Gospel lesson portrays Jesus wrapping up a lesson in early church discipline. “Wherever two or three are gathered in my name,” he says, “I am among them.” While this may have originally been a poetic flourish on a pragmatic exhortation, in the context of this conversation about God and shoes and storms it takes on new meaning.

Where was God in the midst of our storm? He was sitting in that hallway next to me. He was in the back of a city dump truck comforting those who had lost everything. He was in the shelter reassuring evacuees that though separated from family and friends they were never truly alone. He was praying with purpose that the creation he authored would not take the life of another of his children. He was dining with his shoes on. Treading the line between hope and fear as he did on the night of the Passover and the night of the Last Supper and the nights that Montana burned and Mexico City shook.

I’m happy to report that shoes are the only things in closets at my house these days. Houstonians don’t own many coats.

Our hurricane experience has changed us, though. It’s made us more aware of the true meaning of preparedness — best to wear clean socks to bed if you’re going to have to wake with shoes on. More than that, it has taught us to seek out those sacred places in life where God calls us to take our shoes off — Holy Ground.

About Art Callaham

Art Callaham is a religious professional. He’s an amateur at almost everything else. Art lives in Houston, TX and blogs at Late2Church.wordpress.com.