A common accusation against ex-Mormons is that they “leave the church, but can’t leave it alone.” This phrase sounds a lot like “you know you like it.” When reading the stories of lives lived under the Mormon church, imagine your own life lived under such pervasive control. Mormon thought is policed to the point where 12-year-old boys and girls are regularly and formally interrogated by adult male clergy about their sexual fantasies, activities, and masturbation habits.

Would living under such an invasive institution not shape your identity such that it was impossible to simply leave it alone? Could you simply forget or move on from having been a child who was asked by an adult to describe the ways you think about or touch your budding body? Whether it was touched by or talked about with your boyfriend or girlfriend, in excruciating detail? Would you not wonder why so much time was spent on this particular topic in the Bishop’s interview? Whether he, in fact, “liked” it?

Would you not wonder how often this Bishop’s interview added physical sexual assault to verbal harassment?

Further, would you not, perhaps, wonder whether it was moral for you, knowing the effects of such an institution as intimately as you do, to “leave it alone?”

Ex-Mormons are forced to move on with their lives knowing that others are being damaged the way they were. It’s not as if the church has changed because an ex-Mormon once wrote a heartfelt letter of resignation from it. (It’s also not unreasonable to realize the practice of the Bishop’s interview is anything more than ritualized child sex abuse, directly resulting in difficulty enjoying a healthy sexual identity for most Mormons.)

Many ex-Mormons feel a duty to share their experiences in hopes of shedding light on a more than occasionally sinister system that the larger culture knows surprisingly little about. Auto-revelatory stories are often met with gaslighting, character attacks, and accusations of hate speech. Imagine ex-Mormons raised in the church being “Christsplained” by helpful Christians that you “don’t know what Mormons really believe.” The less rosy a Mormon story is told, the less likely it is to be taken seriously.

So, what is my story? I was absurdly devout; when I went to hear Dallin H. Oaks speak to the members in our area and he told us that year’s severe drought was caused by Mormon teenagers having sex, I believed it. SEX → DROUGHT. Check. I elected to take astronomy, like most Mormons in my high school, so that I would have a head start helping my husband run his own solar system once we got to be Gods. Yep. I was so happy I never had to experience getting old, because Jesus was coming again when I was in my twenties, so I’d stay that way forever. Kind of like being a vampire. If ever I did question the church (polygamy in Heaven put knots in my stomach, followed by dreading the Bishop’s interview, which made me squirm, even though I never had much to confess), I “put it on the shelf,” like we were taught.

And like every other ex-Mormon I know, I lost my faith because I learned something about the Mormon church. Unlike some, I didn’t go looking, rooting around in church history to find massacres of non-Mormons in Utah territory or Joseph Smith’s polygamy or the cover-up of a Brigham Young University DNA study which proved Native Americans are not Jewish in descent.

It was a seminary lesson taught to me that broke my unwavering faith.

If I hadn’t gone to seminary class that particular day, at six in the morning before high school just like every weekday, I wouldn’t have suddenly lost my faith at the age of 18 and would’ve gone to BYU, as it had always just been assumed I would.

If I had gone to BYU, Mormonism would likely have remained my core identity, my organizing force in life. But that early Spring morning, I was taught the Latter Day Saint church’s official stance on women. Instantly and instinctively, I knew everything that had made sense of the world for me, everything I had based my sense of self on, was a lie.

It’s hard to come back from that kind of existential free fall. Part of the nausea and motion sickness is still with me.

Sure, I’d been through the awkward object lessons in Sunday school when you see your teacher has brought cupcakes, only to find out that each one has been licked already. Non-virgins, the teacher explains, are like licked cupcakes: who would want them?

This happened regularly enough that I still don’t trust that anyone who comes bearing baked goods has good intentions.

There was also the same lesson regarding a chewed piece of gum, and dating from a father’s perspective being loaning a young man your “prized possession,” a brand new Ferrari, knowing he might very well wreck it.

Though I cringed a bit at “prized possession” and, well, polygamy being God’s will, to be continued once we all got into Heaven (I often thought about one day sharing my husband and how much growth I had to do before I got there spiritually), the licked cupcake metaphor seemed an apt and sensible warning.

When I told my mother that our Bishop made me very uncomfortable, the way he’d needle me to go on and on about every single little thing my boyfriend and I did (necking and petting, at most) in great detail, she said I was uncomfortable because he was a man of God and I was a slut. I was incredibly hurt. I took it to heart. I knew no man wanted a non-virgin; not for a wife. And a wife was what I aspired to be, above anything else.

But it went further. I was taught that God, Himself, turns His back on women who have sex before or outside of marriage. God, Himself, turns His back on women who have been raped.

I remember our seminary teacher suddenly turning solemn and waking all the kids who were trying to hide their sleep by wearing hats and slouching over their scriptures (we thought we appeared to be reading). She had something very important to tell us, something the First Presidency (the highest levels of church authority) wanted us to know.

My seminary teacher said that she knew police were attending D.A.R.E. classes in our schools, and that they were advising kids in the event of an assault not to antagonize the attacker, not to try to fight back. This compliance statistically greatly improved your chances of survival.

But this wasn’t what we were supposed to do. Our teacher made herself very clear. She said the righteous thing to do was “everything in your power” to get murdered instead of raped, because it’s better to be dead than lose your virginity.

I knew she was wrong. I wasn’t a rebellious kid, by any means, nor was I prone to bouts of critical thinking. I knew that if God wanted you dead for getting raped, then he was not moral. Things were spinning out of control. Was the right thing to do, then, to oppose this God?

I thought of all the girls (and boys, whom the lesson was not so much directed at) in that very room at that moment who I knew had willingly given their virginity, some to each other, most to other Mormons. I wouldn’t rather have them dead. They were friends–siblings almost, given the amount of time we were forced to spend together.

Throughout the speech, I stole glances at my friend who’d just that week told me she’d had sex with her boyfriend. I watched him, too. She looked about to cry, while his expression didn’t change.

The most precious thing women have, our teacher explained, is our virginity and our ability to bear children. It hadn’t particularly hit home before, but now suddenly I realized I was being evaluated like livestock. Was I just a tithe-payer generating machine? What about rape survivors? Abused children? The culture I loved, I realized, hated me.

The room was spinning and I felt like I was going to throw up, exacerbated as the teacher continued by “bearing her testimony” that she would rather have buried her gay son than live with his sexuality.

I knew her family well, and had never heard of this son before. Now I knew why.

Things were happening far too fast.

I was always an all-or-nothing thinker. I suppose that’s probably because I was raised in the church, where life is strictly black and white. I didn’t just lose my faith in Mormonism. I lost my faith in God altogether. In the space of about ten minutes, it was gone.

The same way our teacher couldn’t stand to have a gay son, I couldn’t stand to have a bigot God. So I left him behind, unwillingly. It just happened.

I wish I could say it’s all exhilarating when you do get free. A lot of things certainly are: coffee, sleeping in on Sundays, R-rated movies, the thrill of analytical thinking, and your own opinions. But a lot of it is still tortured: sex, ties to community, trust.

I was very lost for a while, just when I was leaving home and needed myself. I had no value system that I’d ever worked out on my own, and the one that was handed to me was clearly flawed, so I floated around in a nihilistic fog through college, when the chances to make mistakes and truly, actually, degrade yourself are plentiful.

In Salt Lake City, a place where every social interaction is organized around a binary Mormon/non-Mormon us versus them pole, I watched Mormons my age, suddenly finding themselves with a little more freedom, flounder in the same sort of fog. We tirelessly fought each other, Mormons and non-Mormons, in the papers, in the legislature, in our homes.

We sneaked cases of Rolling Rock into our dorms. They drank whole bottles of Robitussin. They skirted around the sex prohibition with anal and oral, and hated themselves and each other deeply for it. I had vaginal intercourse, and loved my body for the first time.

One in four women are sexually assaulted during their time in college. Elizabeth Smart was kidnapped, repeatedly raped, polygamously married, and forced to wear a veil. She has spoken out against the “licked cupcake” culture that condemns even her after her ordeal. Some Mormons rally to ordain women. Others march for tolerance of gays and lesbians in the church.

When I was Mormon, women wearing pants to church was unfathomable. Now, on Facebook, I see notices for days of rebellion against church patriarchy by wearing pants to meetings. You can do this: stay and fight, wear pants on certain designated protest days. Or you can walk away, wearing anything you like.

For me, leaving wasn’t much of a choice. My conscience made me leave. I couldn’t live with myself supporting such an organization. It’s only a matter of time until the LDS church experiences a large-scale sex abuse scandal and the extent of its damage in just one area of Mormon life is uncovered.

On days when it’s really bad, I remind myself that if I accomplish nothing else in this life, at least I can say that I stood up and left a church that wishes me dead.

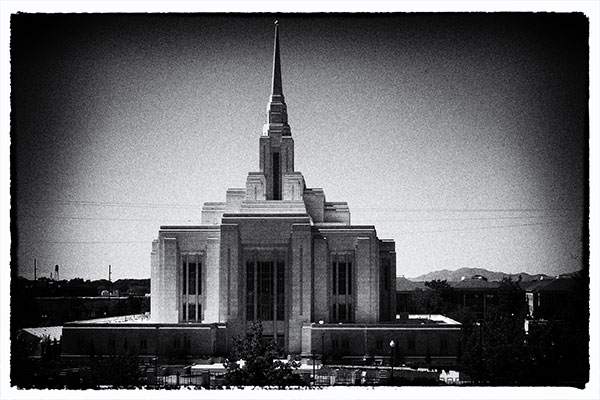

Photo via Pixabay.

About Rachael S.

Rachael S. has officially resigned from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. She writes about religion, sex, and mental health at dearuncledad.wordpress.com.

Leave a Reply