1 Corinthians 14.34−35 reads:

Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.

Here Paul writes in unambiguous terms a dictum applicable not just to a single church, but to “the churches,” repeating his injunction twice: women should remain silent, they aren’t allowed to speak, and then, in case you’re still looking for a way around this rule, he reminds us that “it is disgraceful” for women to speak in church. Paul couldn’t have been any clearer on the issue. Reading the text at face value, there’s simply no room for interpreting away his command.

Despite this clarity, few Christians actually follow Paul’s command. It’s often explained away as a cultural artifact, perhaps addressing a specific situation involving a group of unruly wives in Corinth. But an across-the-board prohibition against women speaking that’s applicable to the modern church? Surely not!

However, there are some significant textual issues behind these verses that cast doubt on whether Paul actually penned them.

First, it isn’t at all clear where these two verses actually belong in the text. Depending on which manuscript tradition you study, these verse appear either after v. 33 or after v. 40. There’s roughly equal manuscript support for each reading, so it’s not so much a careful scholarly assessment as it is an accident of history that they appear where they do in our modern Bibles.

Here’s the two spots where they show up:

33For God is not a God of disorder but of peace — as in all the congregations of the Lord’s people. [34Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. 35If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.] 36Or did the word of God originate with you? Or are you the only people it has reached? 37If anyone thinks they are a prophet or otherwise gifted by the Spirit, let them acknowledge that what I am writing to you is the Lord’s command. 38But if anyone ignores this, they will themselves be ignored. 39Therefore, my brothers and sisters, be eager to prophesy, and do not forbid speaking in tongues. 40But everything should be done in a fitting and orderly way. [34Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. 35If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.] 1Now, brothers and sisters, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand.

These verses work equally well — and equally poorly — in both locations, something unlikely to be true if they were a part of Paul’s original text. Evangelical scholar Gordon Fee noted this fact in his 1987 commentary on 1 Corinthians, proposing that the best explanation for this “moving” text was that these verses aren’t actually original to Paul’s letter — that they are a later addition.

Fee argued that an early scribe wrote these verses in the margins of the letter and that later copyists incorporated them into the main body of text. Fee also noted that such an occurrence resolves the tension with Paul’s earlier guidance in favor of women speaking in church in the form of prophecy. If these verses were a later addition, then Paul wasn’t at all opposed to women speaking in church.

Since Fee’s conjecture in 1987, scholars have discovered manuscript support that lends weight to the argument. Though not conclusive — we still don’t have a manuscript that entirely omits these verses — the evidence against their originality continues to mount.

Let’s take a closer looks at the manuscripts:

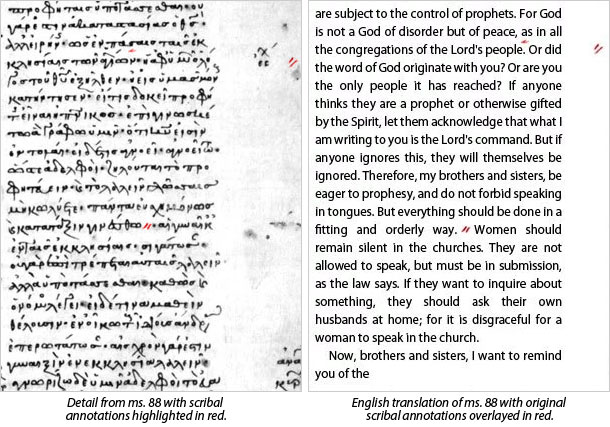

Minuscule 88

Minuscule 88 is a Greek manuscript from the 12th century. In this manuscript, 1 Cor. 14.36 comes directly after v. 33, while our text in question, vs. 34–35, comes after v. 40. However, vs. 34–35 are separated from the main text by a double slash. These slashes correspond with a smaller double slash that appears earlier on the page at the end of v. 33 and also in the right margin of v. 33.

It seems that the scribe first wrote vs. 33–40 and omitted vs. 34–35, and then realized that omission only after he had already begun to write v. 36. To correct this error he added them in after v. 40 and made note of where they should be inserted into the text with the double slashes at v. 33.

Why would he do this? The most likely explanation is that one of the texts he was copying from didn’t contain vs. 34–35 at all. He realized too late that the manuscript he was copying from contained a non-traditional reading, so he “fixed” it by adding the missing verses and marking where they should go. This isn’t conclusive evidence that vs. 34–35 aren’t original, but it’s still a tantalizing piece of the puzzle that points towards the existence of a manuscript without these verses.

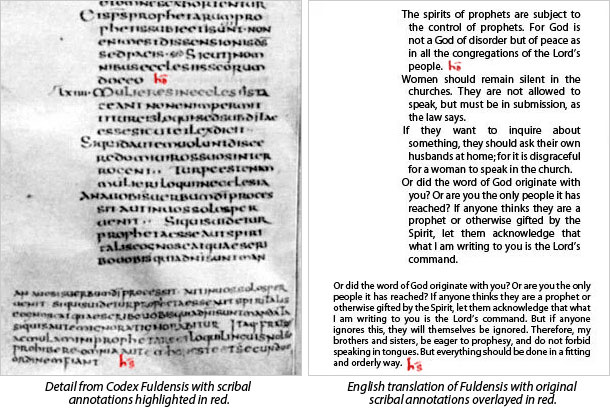

Codex Fuldensis

Codex Fuldensis was meticulously compiled by the Italian Bishop Victor of Capua in the mid-6th century and is one of the earliest Latin manuscripts of the New Testament. In Fuldensis, following 1 Cor. 14.33 is a marking that redirects the reader to the bottom margin where vs. 36–40 are written out. It seems likely that the scribe, probably under the direct guidance of Victor, was correcting his original text and designated a replacement text, possibly based on manuscripts that we no longer have. He’s essentially saying that vs. 36–40 are supposed to directly follow after verse 33 and over-write vs. 34–35.

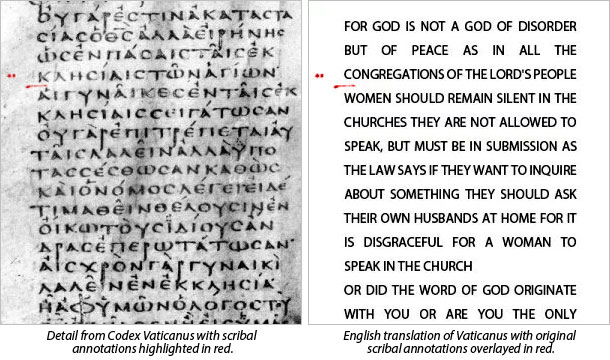

Codex Vaticanus

Codex Vaticanus is one of the oldest manuscripts of the entire Bible — from the mid-4th century — and is one of the best Greek texts available to us. In the left margin of 1 Corinthians 14 are two dots aligned with verse 33 and a horizontal bar between verses 33 and 34. Similar markings appear throughout the text of Vaticanus that correspond to known textual issues. The scribe is probably marking where he is aware of a “problem” with the text. In this case, the only potential issue that we are aware of in regards to these verses is that they might not have been part of the original text. It is likely that the scribe of Vaticanus was aware of differing manuscript traditions — some of which omitted these verses entirely — and was making a notation of the existence of these textual variants.

This is only an abbreviated overview of the evidence that suggests 1 Corinthians 14.34−35 might not have been part of Paul’s original letter. There continues to be a lively scholarly debate about these verses that has yet to reach a consensus — and given the paucity of resources, may never reach a consensus. But this lack of clarity shouldn’t leave us simply scratching our heads. Rather, it should cause us to ask important questions about the role of women in the church, about how we interpret and understand the Bible, and ultimately about how we understand God.

Further Reading

- Gordon D. Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, 1987

- Philip B. Payne, Sigla for Variants in Vaticanus, and 1 Cor. 14.34−35, 1995

- Philip B. Payne, Ms. 88 as evidence for a text without 1 Cor. 14.34−35, 1998

- Philip B. Payne, The Originality of Text-Critical Symbols in Codex Vaticanus, 2000

Dan Wilkinson

Dan Wilkinson

Dan is the Executive Editor of the Unfundamentalist Christians blog. He is a writer, graphic designer and IT specialist. He lives in Montana, is married and has two cats.

Leave a Reply