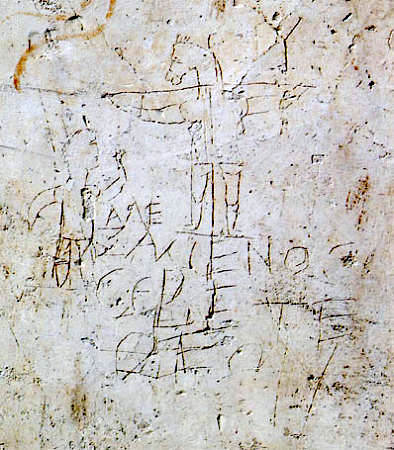

Ancient graffiti from the Palatine Hill in Rome, depicting a man with a donkey’s head being crucified and the Greek phrase Αλεξαμενος ϲεβετε θεον — “Alexamenos worships (his) god.” Photo from Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Today is Good Friday, the day on which Christians mark the occasion of Jesus’ crucifixion. The precise day and time varies depending on which Gospel you read, but according to the historical methodologies accepted by scholars of the ancient world, there is perhaps no event that more certainly occurred in antiquity.

It is hard to emphasize just how striking a situation early Christians were in, owing to the crucifixion of their founder. The cross today is almost universally recognized as a symbol for Christianity, but that was certainly not the case in the first century, nor even in the first few centuries after Jesus died.

Scholars have long seen the crucifixion of Jesus as highly probable historically, because crucifixion was such a public, shameful, and politically charged method of execution. This is not, as the “criterion of embarrassment” sees it, something that a group of people would make up. As a scholar of ancient Rome, I have to agree: I cannot imagine a scenario more fraught with problems than one in which your chief figurehead had been crucified, and it seems clear from much of Christian literature, from the Gospels themselves onward, that Christians were very concerned about the image this portrayed and significantly invested in making Jesus appear not at all worthy of any such execution.

Whether one thinks he was, in fact, worthy of execution – from the standpoint of the Romans, of course – typically has more to do with one’s politics and theology. Progressive Christians, like Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, have long held that Jesus’ worldview did, in fact, contradict the imperial ideology of the Romans and so they considered him, and the crowds he was increasingly drawing, as sincere threats.

I tend to agree with this. In spite of the Gospel writers’ attempts to exonerate Rome via a penitent Pilate and lay the blame for Jesus’ death at the feet of the Jews – something that has had atrocious consequences throughout history – the crucifixion stories, alongside contemporary accounts of the region and its politics, without doubt reveal Roman ideologies and tactics that coincide with what we know of them from the broader history.

Crucifixion was not the easiest way to execute someone – there are far easier and faster ways. Crucifixion was not just about getting rid of someone, it was about sending a brutal message to everyone else as to what happens to those who undermine Rome’s imperial authority. It’s for this reason that other notable figures who suffered crucifixion – like Spartacus, the leader of a slave revolt, for example – were hung upon their own crosses.

Jesus was not just a nuisance, nor was his execution one brought about by his religious idiosyncrasies, as many Christians asserted then and still believe. Rome rarely cared about its subjects’ religious beliefs; it was rather their actions that disturbed them – actions like meeting in large groups, gathering crowds, or declaring someone other than the emperor as “king.” These are all things that would prompt a Roman governor like Pilate – who is far more brutal in other sources than he appears in the Gospels – to summarily crucify someone without a moment’s hesitation.

Jesus was more than an annoyance; to the Romans, he was a terrorist – a religious fanatic who would no doubt try to overturn their social order if allowed to gain too many followers. It’s clear that the title “King of the Jews,” probably shouted by at least a few (if not multitudes) on Palm Sunday, irked the Romans: when they crucified him, that’s what they put on his cross (the origin of the INRI now common in Christian iconography – Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum). That titulus was to announce the reason for his crucifixion, and its inevitable failure in the face of Roman power.

Moreover, Jesus was crucified alongside two others who were also most likely accused insurrectionists. Though the Gospel accounts are often translated to suggest they were “thieves” or “bandits,” the Greek word λησταί is used by the contemporary Jewish historian Josephus to refer to insurrectionists against the Romans. It was only a generation after Jesus’ death, after all, that Jerusalem was leveled by the Romans thanks to uprisings there. First-century Judea was not a calm, tranquil place.

So the Romans were brutal, so what? We all pretty much know that. Yet think about it: Roman imperial ideology was so strong, even among those it victimized, that the writers of the New Testament, not to mention apocryphal Christian literature (which would go so far as to make Pilate a bona-fide convert and martyr), went out of their way to soften or excuse Jesus’ shameful execution – to make it something else entirely, such that the Jews onto whom the blame had shifted would deal with a blood libel up until today.

That’s the problem with ideology, no matter how brutal: it’s often invisible, even to those victimized by it. As we mark the occasion of a man viciously executed by a government that perceived him to be a fanatical enemy combatant, we might pause to wonder and raise our consciousness about what other injustices our own empire commits, even if we often remain blind to them.

About Don M. Burrows

About Don M. Burrows

Don M. Burrows is a former journalist and current college preparatory school teacher. Don holds a Ph.D. in Classical Studies from the University of Minnesota. A former Christian fundamentalist, Don is now a member of the United Church of Christ and contends most firmly that the Bible cannot be read or explored without appreciating its ancient, historical context. Don lives in Minneapolis with his wife and two young children. Don blogs at Nota Bene and can also be found on Facebook.

Leave a Reply