I love the Lord’s Prayer.

The translation of it now universally recited in the English-speaking world holds a poetic, lilting quality that makes its recitation a cathartic ritual even if one holds sincere doubts about its specific words.

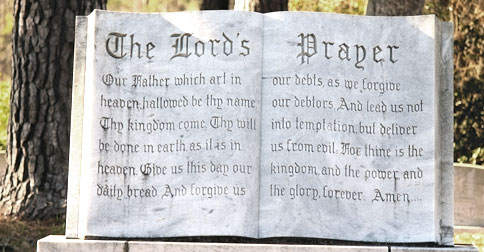

But what exactly are those words?

Many Christians, if not most, have experienced the embarrassment of rehearsing aloud – and it always feels super loud, right? – the wrong choice of “debts” or “trespasses” when the service at a new church turns to the Lord’s Prayer, as it so often does. It always feels as though – even if you managed to discreetly escape the Visitor’s Sticker they wanted to put on your lapel – you have just declared in no uncertain terms that you are an outsider.

Yet despite this common experience, few perhaps realize that this confusion between debts and trespasses reflects an inconsistency in the New Testament itself. It’s Luke – and Luke alone – who records that Jesus instructed us to pray to God to “forgive us our sins,” or ἁμαρτίαι (hamartiai), the word we translate as “trespasses.” Yet he does not use the same word for what we are to do for others. That word remains “debtors” (ὀφείλοντι, opheilonti) in much the same way Matthew records that we are to forgive the “debts” (ὀφειλέταις, opheiletais) owed to us.

So why do so many churches use “trespasses” in both cases? Clearly it’s more poetic for them to be in parallel, even if they never appear that way in the New Testament, and many have argued that the notion of “debt” among Jews at the time would have had a clear allusion to “sin.” Yet debt itself was a big issue among the ancients, and a highly political one at that.

Indeed, if one reads the Lord’s Prayer in the original Greek, and keeps in mind the reception it would have received among the Romans running things at the time, it becomes apparent just how politically charged the whole entreaty really is.

First, we should point out that while many things attributed to Jesus in the Gospels (including some of his most famous remarks) are literary and not historical and thus were perhaps never uttered by him, the Lord’s Prayer, in rough outline, is broadly thought to have come straight from Jesus. It is generally agreed to have come from Q – the common source used by Matthew and Luke when they were not using Mark, as it appears in Matthew and Luke in striking similarity but not in Mark. Likewise, it is typically also assumed that Luke represents the older core of the prayer, as his is shorter and less elaborate, even though his use of “trespasses” rather than “debts” in that first instance discussed above is probably something he himself did.

If we look at just Luke’s prayer, and change his “trespasses” back to “debts,” we get something that is translated more literally thus:

Father,

May your name be holy.

May your kingdom come.

Give to us our daily rationed bread,

And forgive us of our debts,

For even we forgive all those indebted to us.

And may you not lead us into trial.

Note that one of the first things to go are the qualifiers about God and his kingdom: it’s no longer “who art in heaven,” and his will is not to be done here “as in heaven,” but rather the message is left straightforward. This makes more sense to me from an ancient mindset: even if Jesus did speak of eternal life elsewhere, the ancient peasant’s immediate needs were of immediate concern (hence the petition for daily bread).

Note too that Jesus’ followers were asked to entreat God to bring about his “kingdom.” In a day and age when the word “kingdom” has become the stuff of fantasy and legend, it’s perhaps easy to forget what a politically charged word it was at the time. The word, βασιλεία (basileia), contains the same root as the basilicas erected in the forum by the Caesars to honor themselves. This is not a neutral or merely religious term. It’s a highly political one.

But what of debt and bread – surely these are just everyday petitions?

Not really, no – at least not to the Roman ears that were clearly keeping tabs on Jesus. In ancient Rome, there were perhaps no two bigger political footballs than that of debt and bread.

Bread, in the form of grain distribution for daily sustenance, was a highly charged political issue in Rome, beginning with the lex frumentaria passed by Gaius Sempronius Gracchus in 123 BCE, which assured citizens of wheat at a subsidized price. Indeed, a quarter century later Lucius Saturninus went further, proposing a grain law to provide for the people, a matter that quickly became controversial. Julius Caesar as consul in 59 BCE threatened to make grain completely free for the public and his political ally, the tribune Clodius, made it so with the Lex Clodia the next year. Thereafter, Suetonius writes that Caesar “distributed [grain] to them without stint or measure.”

From then on the distribution of grain would be a political one, with maneuvers to limit recipients but not to remove it completely. And who can forget the famous “bread and circuses” the public would demand from the emperors thereafter? Bread and grain were not merely innocent matters for the everyday peasant or citizen in antiquity – these were matters of daily survival for the masses, and with the advent of the empire, that is where the imperial leaders drew their support – not from the landed aristocracy, with which they had continual conflict, but with the everyday people on the streets.

Debt, too, was a matter of Roman political importance, and in much the same way. But first of all, why did we end up with this confusion between “debts” and “sins” in the first place?

Typically, this has been ascribed to Luke’s more Gentile focus. While many scholars think Matthew took for granted that his audience would understand that the Greek word for “debts” would refer to “sins” as it often does in the Jewish tradition (even though it’s rarely if ever used in such a way by other Greek authors), Luke figured he needed to make that clear himself, and so he apparently changed “debts” to “sins” to make it more sensible to his Gentile audience.

Nevertheless, “debts” remains and very well may have been the Greek manner in which this would have been reported or overheard by the Romans. And how much political significance did debt relief have among the Romans? A lot.

The proposal for tabulae novae – “new tables” or “clean slates” we might say – came up frequently in Roman history among would-be political movers, but most especially in times of civil conflict. In the time of the Catilinarian conspiracy, according to some interpretations, the indebted aristocracy used debt relief as a rallying cry. And Cicero worried often in his letters about tabulae novae around the outbreak of civil war in 49 BCE.

One story from our primary sources suffices to show just how seriously the Romans took this, even if the tale is mere literary fiction. In 6.14-20 of Livy’s histories we get the tale of Manlius Capitolinus, so named because he repelled the Gauls from the Capitoline. Manlius ingratiates himself among the plebs by denouncing debt imprisonment and draws great crowds as a result. Manlius was eventually tried for kingly aspirations and was executed (hurled from the Tarpeian Rock). This combination of factors recurs here and elsewhere in Roman political upheavals: promises of grain or debt relief, crowds, and eventual trial on the part of the guilty party for “king”-like designs.

That leaves us with the ending of the prayer – a strange entreaty not to be led to “trial.” This is typically translated as “temptation,” and it might mean that. But the word πειρασμόν (em>peirasmos) is in fact a legal one, and whatever metaphorical temptation Jesus and his followers might have meant, to the Romans, this would have sounded like a wish to remain out of legal trouble. And of course, given the turmoil of the time – with crucifixions happening so regularly that officials were once said to have run out of crosses – it’s not unheard of that Jesus and his followers would have wished to escape notice from their brutal overlords.

And Matthew’s addition to be “delivered from evil” doesn’t help matters, either. What is translated as “evil” is really the word “πονηροῦ” (ponērou). But πονηρός (ponēros) is an adjective, not an abstract noun like “evil,” nor is it the word most commonly translated into “evil” – κακός (kakos). There is even an article in Matthew, so this seems to be referring to a person, and not “the evil one,” either, since πονηρός (ponēros) typically carries the sense of “wretched” or “cowardly” or “worthless.” Is this referring to Satan? Maybe – your guess is as good as mine, or anyone else’s: it’s just not that clear. And it probably wouldn’t have been too clear to the Romans, aside from seeming like a general insult. Coming on the heels of avoiding trial, you can imagine what they may have thought.

The last part of the now-famous prayer: “for thine is the Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory Forever,” is not found in either gospel – indeed, not found in the Bible at all. Rather, it comes from the second-century church teaching called the Didache, which features the Lord’s Prayer in its entirety. Some scribes of Matthew appear to have added it later to Matthew, which accounts for its appearance in later manuscripts (and translations like the King James Version) but not our earliest ones, nor in today’s translations that rely on modern textual criticism.

But the core of the prayer, as gleaned from Luke, is clear: kingdom, bread, debt, and trial. Nowhere in the Roman world in the first century would these four words be said without at least some political reverberations. Whether we think Jesus used these words apolitically or as a deliberate revolutionary probably has more to do with our politics than our piety. But it would not have been heard by the wider world at the time as the gentle meditation it so often feels like today.

And yet even today, debt relief and food for the poor, even when basic human compassion should render them spiritual no-brainers, remain political issues. We can recite the prayer as mere ritual if we wish, allowing its droning poetic qualities to comfort and calm us. We can look beyond the surface meanings of the words and the cultural and political contexts that would have certainly greeted them at the time, in an attempt to make them less immediately applicable today.

Or, we can take the Lord’s Prayer seriously, and question whether we truly mean its entreaties to take hold here on Earth as well as in heaven.

About Don M. Burrows

About Don M. Burrows

Don M. Burrows is a former journalist and current college preparatory school teacher. Don holds a Ph.D. in Classical Studies from the University of Minnesota. A former Christian fundamentalist, Don is now a member of the United Church of Christ and contends most firmly that the Bible cannot be read or explored without appreciating its ancient, historical context. Don lives in Minneapolis with his wife and two young children. Don blogs at Nota Bene and can also be found on Facebook.

Leave a Reply