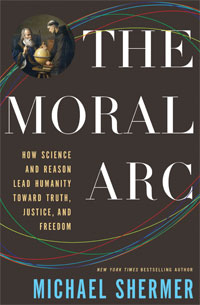

Michael Shermer is an optimist. The outspoken skeptic and author of the new book, The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom (Henry Holt, $32), sees humanity – and indeed all of life – as progressing on a steady and incremental trek toward a better moral, social, political, technological and economic existence.

Shermer acknowledges the many challenges to his optimism: our history is plagued by violence, hatred, ignorance, superstition and oppression. But through his hefty and ambitious volume, Shermer argues that the only reliable way to conquer such evils is through science and reason. For Shermer, the Scientific Revolution and the dawning of the Age of Reason and Enlightenment stand as the pivotal moments in all of history: these are the events that have catapulted us forward toward an ever brighter future. It is only through the “scientific understanding of the causes of evil and the rational application of the political, economic, and legal forces” that we are able to “bend that arc ever upward.”

According to Shermer, the greatest threat to science and free inquiry are authority and dogmatism, and these negative forces are primarily manifested in religion, most significantly in the form of Christianity. He argues that religion’s tribalistic and xenophobic roots establish it as inherently opposed to true moral progress, and that we must free ourselves from these limitations:

Never again should we allow ourselves to be the intellectual slaves of those who would bind our minds with the chains of dogma and authority. In its stead we use reason and science as the arbiters of truth and knowledge.

Shermer devotes a significant section of his book to documenting these negative aspects of Christian belief, labeling the Bible as “one of the most immoral works in all literature” and taking Jesus to task for failing to overturn the moral shortcomings of the Old Testament.

He deconstructs the Ten Commandments and offers up his own “provisional rational Decalogue” that he summarizes as an attempt “to expand the moral sphere and to push the arc of the moral universe just a bit farther toward truth, justice, and freedom for more sentient beings in more places more of the time.”

It is certainly true that secular values have been powerful forces against slavery and racism, and have effectively championed women’s and LGBT rights – and that Christians all too often have found themselves on the wrong side of these issues. Shermer is hard on Christians, but it’s tough to argue that he’s unfair to us. His challenges are ones that Christians need to pay attention to, that we need to wrestle with and not simply brush aside as irrelevant or misinformed.

Though Shermer spends much time decrying forces that have opposed science and reason, his ultimate goal is to show that

the arc of the moral universe bends not merely toward justice, but also toward truth and freedom, and that these positive outcomes have largely been the product of societies moving toward more secular forms of governance and politics, law and jurisprudence, moral reasoning and ethical analysis.

Does he succeed in defending that thesis?

As a pessimist, I have a difficult time accepting Shermer’s conclusions. Though humans have shown themselves to be startlingly resilient, and though we have made great advances in certain fields, we clearly have an alarming proclivity for screwing things up.

Shermer’s virtually unbridled optimism brings to mind pre-First World War naïveté as described by historian G.P. Gooch:

I grew to manhood in an age of sensational progress and limitless self-confidence. Civilization was spreading across the earth with giant strides; science was tossing us miracle after miracle; wealth was accumulating at a pace undreamed of in earlier generations; the amenities of life were being brought within the range of an ever greater number of our fellow-creatures … There was a robust conviction that we were on the right track: that man was a teachable animal who would work out his salvation if given his chance; that the nations were on the march toward a larger freedom and a fuller humanity; that difficulties could be taken in their stride … We realize today that we were living in a fool’s paradise …

–G.P. Gooch, “The Lessons of 1914-1918,” Current History, August 1934

We’re only 100 years removed from a war that, for Gooch and many others, shattered the myth of human progress. And those subsequent years ushered in a Second World War, a Cold War and countless other conflicts and atrocities. It takes a generous dose of hubris and a thick pair of rose colored glasses to downplay our recent history.

And, contra Shermer, our future also holds a sobering outlook. There are good reasons that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently nudged their Doomsday Clock two minutes closer to midnight, stating:

In 2015, unchecked climate change, global nuclear weapons modernizations, and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals pose extraordinary and undeniable threats to the continued existence of humanity, and world leaders have failed to act with the speed or on the scale required to protect citizens from potential catastrophe. These failures of political leadership endanger every person on Earth.

I hope that Shermer is right, and that such dire warnings never become catastrophic realities. I hope that we will continue to move forward, albeit in fits and starts, reaching ever greater heights of human achievement, riding a moral arc towards ever greater peace and well-being.

Only time will tell which understanding of our world is the right one. But in the meantime, I wholeheartedly agree with Shermer that it’s incumbent upon all of us, regardless of our religious faith or lack thereof, to embrace science and reason, to eschew dogmatism and oppressive authority, and to fight for freedom and justice.

Dan Wilkinson

Dan Wilkinson

Dan is the Executive Editor of the Unfundamentalist Christians blog. He is a writer, graphic designer and IT specialist. He lives in Montana, is married and cares for several cats.

Leave a Reply