Christians have an equivocal relationship with the Bible.

Some view the Bible as the absolute, authoritative, inerrant, infallible Word of God, but yet often fail to read it. New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman recounts that the majority of his students believe that the Bible is “the inspired Word of God,” yet far more of them have read the entire Harry Potter series than have read the entire Bible. He concludes that “my students have a much higher reverence for the Bible than knowledge about it.”

At the other end of the spectrum are those who claim to follow Jesus, yet dismiss the Bible as a slapdash amalgamation of outdated and naive writings that have little direct relevance to our lives today. For them, there may be some inspiration to be found in a few of Jesus’ sayings, but modern life is best lived not in light of Scripture, but at a good distance from it.

For many Christians, the best approach to the Bible is to simply avoid it: it’s too confusing, too long and far too messy. It’s been, they feel, the source of too much pain and suffering. It harbors memories of bad sermons and abusive childhoods. It’s been used — and continues to be used — to support the marginalization of countless people based solely on their race, gender or sexuality.

For many Christians, reading the Bible — the very same Bible that has served as the central text of the Christian faith for thousands of years — is a task reserved for fundy wackos or ivory-tower scholars.

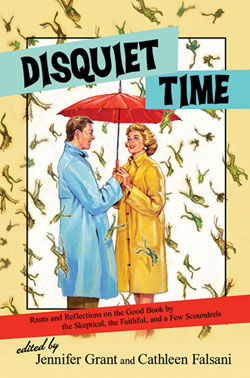

The just released book Disquiet Time: Rants and Reflections on the Good Book by the Skeptical, the Faithful, and a Few Scoundrels (Jericho Books, $24.00, B&N, Amazon), edited by Jennifer Grant and Cathleen Falsani, lands a sockdolager to the notion that modern Christians can’t have a robust, meaningful and honest engagement with the Bible.

Wrestling with Scripture is a task that all Christians are called to engage in, and the forty-six essays collected in this volume serve as prime examples of what it means to grapple with the truths contained within the pages of our Holy Book.

The authors enjoin us to share in their doubts and questions, their fears and anxieties, their hopes and joys. They ask us to love the Bible for what it is, not as a pristine and sacrosanct object worthy only of pious veneration, but as a living book that, though it may challenge and confuse us, offers boundless opportunity for faith and growth.

In “Why Isn’t the Link to the Diving Salvific Download Working?” Margot Starbuck discusses 2 Corinthians 3:18 and questions the doctrine of sanctification:

So I guess I’d have to say that the main thing that keeps me from recognizing and embracing the reality of ongoing sanctification is…all the evidence.

Karen Swallow Prior expounds on the role of poop in Scripture in her essay “The Bible: It’s Full of Crap,” discussing such scatological passages as Deuteronomy 23:12-13, Judges 3:21-22 and Isaiah 36:12 and finding lessons in the dung:

Just as our bodies need to be rid of the waste that would otherwise be poison, so, too, must we rid ourselves of spiritual and emotional waste that would otherwise erode our souls. Our need to eliminate also serves as a constant check on human pride. It is a humbling act, which is why we both hide these functions and flagrantly joke about them, too.

Jay Emerson Johnson, in “Apocalypse Later,” engages with Revelation 13:18. He recounts an adolescence defined by obsession with end-times Christianity and filled with an “ambient sense of fear.” But his apocalypse ended up being a personal one, not a Rapture of the Church, but instead a personal apocalypse of coming out as gay: “Moments of apocalypse unfold at their own pace, and as some worlds fall, others rise up to take their place.”

Cathleen Falsani, reflecting on Psalm 139, writes with salty honesty:

God knows me. All of me. Every inch. Every hair. Every thought. Every zit. Every fart. Every step. Every breath. Every hope, fear, sorrow, joy. Every Everything.

King David knew this, and that brother was a major fuckup. He did some horrible shit, and he suffered the harsh consequences, but they didn’t include God throwing up God’s hands hands and stomping away in a huff. God was there when David made epic mistakes, God was there for the ensuing heartbreak, and God was there when David got back on his feet, righted his course, and walked on.

Bill Motz’s contribution, “Daydreaming of Bed Linens,” centers on Acts 10:9-16 and offers a summary of what so many Christians deal with when reading Scripture:

What used to seem so clear-cut and focused now feels murky and muddled. It’s like being in a love-hate relationship with a dear old friend: some parts of the text fill me with joy and an overwhelming sense of truth, others anger me and make me feel that there’s no way God could ever have intended them to be included. Though I try to keep the discipline of daily study alive, I’ll admit to more than a little trepidation when I reach for my Bible.

This collection of compelling stories, biblical insights and honest reflections is an extended invitation to reclaim the Bible for our own, to read it with new openness, to be willing to question and doubt, to join the great community of believers — past and present — in wrestling with the meaning of Scripture. And to all of us Falsani and Grant offer these words of encouragement:

Remember: even if you end up feeling like a cowboy riding an ostrich into the sunset, you are not alone in this. And when it comes to the greatest concerns, biggest questions, and gravest doubts about the Bible, you have the right and freedom to voice them.

Find out more about Disquiet Time at disquiettime.com.

Dan Wilkinson

Dan Wilkinson

Dan is the Executive Editor of the Unfundamentalist blog. He is a writer, graphic designer and IT specialist. He lives in Montana, is married and lives with two cats.

Leave a Reply