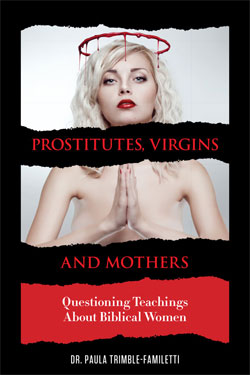

In Prostitutes, Virgins and Mothers: Questioning Teachings About Biblical Women (Personhood Press, $16.95), Dr. Paula Trimble-Familetti sets out to do nothing less than overturn six thousand years of patriarchy, misogyny, and marginalization of women within Judaism and Christianity.

Does she succeed? Of course not: no single book can undo what has become so ingrained in our culture and religion. But she does add a powerful voice to the on-going fight for gender equality within the church, providing an accessible, thorough and Christocentric presentation of feminist theology.

Dr. Trimble-Familetti’s book tackles the issue head-on by re-telling, re-contextualizing, and re-interpreting the stories of virtually every woman in the Bible. Her calling to tell these stories is a passionate one:

I am fed up with traditional interpretations of Scripture. I believe there are different ways to interpret the Scriptures, interpretations from the perspective of a twenty-first century woman, a perspective vastly different from that of a first-, second- or any other -century man. I write this book because my God, my Creator, in whose image and likeness I am created, has called me to write it.

Trimble-Familetti crafts first-person narratives that wrestle with the issues and challenges faced by women in the Bible. Though the accounts are necessarily speculative, she nevertheless strives to retain fidelity to the text as we have received it as well as the socio-historical context in which the stories take place.

These stories represent a middle ground between the academic rigor of Phyllis Trible’s Texts of Terror and the creative speculation of Galina Vroman’s Sarah’s Story. Trimble-Familetti’s re-tellings are straightforward and accessible, while still challenging us to reassess the female protagonists in the Bible.

Through telling the stories of Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, Tamar, Ruth, Bathsheba, Mary, Mary Magdalene and many more — including, perhaps most importantly, Eve — she causes us to read the Bible anew, to set aside “the layers of patriarchal interpretation [that] get encrusted so thickly that we do not even know why we believe what we believe.”

Trimble-Familetti also tackles the “clobber passages” of gender equality, carefully parsing the Biblical texts that are so often used to argue for patriarchy. She provides a brief survey of the misogyny of the church fathers: “What the ‘Church Fathers’ had to say about women is shocking!” and discusses the notion of biblical family values: “A call to biblical family values is usually a call for women to retreat from the public sphere and a call for women’s submission and subordination in the home and in the church.” She closes the book with a presentation of how we received the Biblical texts and an overview of beliefs about the nature of God.

Throughout the book Trimble-Familetti is careful to frame her interpretations with the teachings of Jesus. For her, Jesus taught a powerful message of freedom, equality and reconciliation:

Jesus does not insist on the submission or subjugation of women. Rather, Jesus calls for equality of the man and the woman created male and female in the image of God from the beginning.

And it is in the person of Jesus that she finds the ultimate impetus to fight for change:

The mission of Jesus was, as ours should be today, to change structures of injustice and oppression.

One may certainly quibble with Trimble-Familetti’s exegesis and interpretation of certain passages and perspectives — these are often complex issues that defy perfunctory explanations — but that would be missing the point. Trimble-Familetti doesn’t want us to blindly accept her readings of these texts. She doesn’t want us to blindly accept any reading of the text, and especially readings that are the product of thousands of years of institutionalized patriarchy. Instead, she asks women (and men!) to read the Bible anew, while challenging our assumptions and asking tough questions:

This work is a call for biblical literacy. It is a call for women to interpret the text for themselves, in the light of theological scholarship, archaeological evidence, historical setting and the intention and audience of the author.

Trimble-Familetti asks us to move beyond the status-quo of thousands of years of androcentric Christianity and use our “God-given wisdom to make sense of text and answer the question, ‘Why do we believe what we believe?'”

Will we accept her challenge?

Dan Wilkinson

Dan Wilkinson

Dan is the Executive Editor of the Unfundamentalist blog. He is a writer, graphic designer and IT specialist. He lives in Montana, is married and lives with two cats.

Leave a Reply