This guest post is by UC supporter Pete Lefevre.

Out of a morbid sense of curiosity, I watched the Bill Nye/Ken Ham debate this past week. For me, the origins of our earth and our species have been amply explained through scientific inquiry and those who argue for a 6,000-year-old earth — who treat Genesis as a science and history textbook — have not fully considered the numerous and powerful arguments that might disturb their closed system.

That accusation might well be hurled back at me, so if you’ll allow me some special pleading, I was an adherent to the creationist view for many years. I’ve spent inordinate amounts of my life in American Evangelical Conservative Protestant churches. While this particular subculture of religious expression may not have a printed list of required political, historical, and scientific beliefs I can assure you that if you show any deviance from the expected norm (if, for example, you accept observation of redshift as a reliable dating mechanism for the universe, or accept natural selection as an explanation for the development and variety of life) you may find yourself isolated if not shunned. These churches are not open-ended discussion groups. It’s believe or leave.

So I suited up, showed up, and saluted the flag in a manner of speaking. But my inveterate reading habits did me in. I took great comfort and courage from much of the Bible. I also took great comfort and courage in reading Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Michio Kaku. There came a day when I could no longer take seriously the claim that the Bible is a historical account of the earth’s creation or of humanity’s appearance on it. My struggle to fit measurable observations of the universe into the fragmentary and superficial depiction of its creation in Genesis became too difficult. If you believe God created the world 6,000 years ago, then you must believe in miracles. And if you believe in miracles, then it’s completely possible that God created the world 6,000 years ago. A perfect circle. An echo chamber, actually.

Once I stepped away from the echo chamber, I suddenly found myself starved for science. Spending all those years in a realm of guesswork, speculation, and the adamant assertion of opinion as fact, I suddenly found enormous relief in simple statements of unshakable clarity. Light moves at 186,000 miles per second. To anyone’s knowledge it always has and as far as we know it always will. There is no room for debate here, no second opinion, no court of appeal. Blessed assurance, light moves at 186,000 mps.

Yet …

I had to watch the debate and I wanted Ham to do well. I wanted to hear a legitimate case. It had to be scientific. It had to be unshakable. I wanted to hear him out without a dismissive attitude, without condescension, without the unwarranted pride that can accompany a freelance writer armed with bullet points forged out of a fondness for trade paperback non-fiction.

The more I listened, the more I realized my long flirtation with the creationist viewpoint was the infatuation of a teen who had found his first explanation of origins. I was too intimidated to wrestle with Darwin. Big words. Hard concepts. Easier to just take Genesis at its word and move on with my life.

More accurately, my acceptance of Genesis as a literal account seemed rooted in fear. Fear of angering a jealous, all-powerful, and potentially rage-filled God, fear of social isolation, fear that rejection of creationism would lead to rejection of other things in the Bible, like love, joy, and peace. I mean, once you open the gate …

I had to realize that these perceptions I had were disfiguring me. They weren’t helping me grow, they were stifling my growth. And it was time to get up, clench my fist and say, “No more, I’ve had enough.” This was made abundantly clear as I listened to Ham and Nye. When you start with the perspective that the Bible is inerrant, historically and scientifically, any contrary evidence has to be explained away. The explanations sounded plausible enough when humanity knew much, much less about the cosmos and about biology. With every scientific advance, though–the heliocentric solar system, the relativity of space and time–the fundamentalist was faced with two choices: find ever more implausible explanations, expand Biblical interpretation to make room for the new facts, or question one’s own preconceptions.

Ham has fully committed to implausibility. Take for example the back-and-forth about Noah’s ark. The story as told is in primary colors. It is simple in the way Aesop’s fables are simple. It is not superficial, or unintelligent. It’s just simple. Yet in order to reconcile belief in a young earth with the incomprehensible number of living organisms (and the equally incomprehensible number of organisms that have gone extinct) Ham and others must read deeply between the lines of this story: “Kinds” are not species; who are we to say what kind of shipwright Noah was?; God exists, and He works miracles, so a boat with 14,000 animals on it floating for a full year is completely possible. These assertions, patched together out of pious guesswork, aren’t in the Bible, but Ham is quite willing to reach outside his text to create fantastical scenarios in order to protect his belief system. Such embarrassing speculation diminishes the Bible rather than honors it.

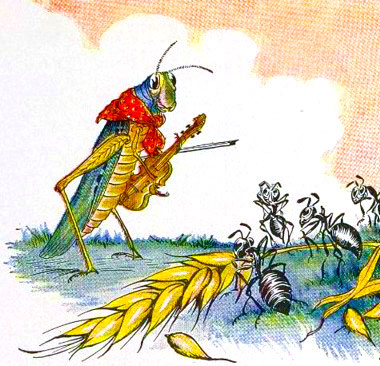

Listening to Ham convinced me more than ever before that he, and others of his convictions, have completely missed the point about both science and faith. The well-known Aesop told a fable about an ant and a grasshopper. The ant collected food during the summer and the grasshopper was lazy. Winter came, the ants had food, the grasshopper didn’t, the ants lived, the grasshopper died. Now, what comes at the end of the tale? All together now: “And the moral of the story is…” In this case, it’s Don’t Be Lazy.

Talking with fundamentalists, I feel like I am having someone tell me that the point of the story is that there was a real ant and a real grasshopper and the insects actually had a verbal discussion about the moral implications of sloth. True interaction isn’t possible because the basic principles of discussion aren’t shared. Ham wasn’t making a scientific case; he was defending the Bible using scientific language. His is a god of nursery rhymes and blocks, defended by lip service to science and history. As more observations are made, as more advances in measurement are secured, he will find himself–as religious extremists found themselves when faced with Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, and Einstein–forced into ever more absurd positions, or compelled towards violence and intimidation. One must wonder how absurd the positions will get before fundamentalists too find blessed assurance in the speed of light.

Leave a Reply