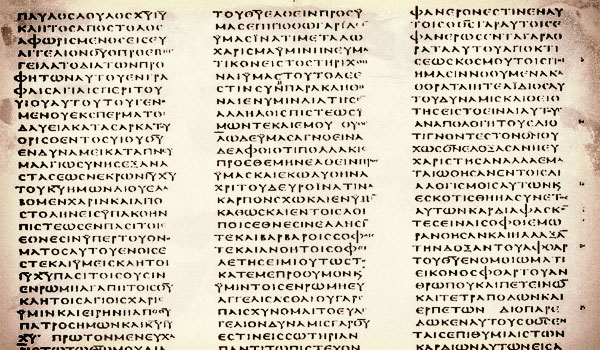

Romans 1 from Codex Vaticanus, c. 300-325, Public Domain.

Whenever I’m debating with someone who authoritatively declares that the Bible condemns homosexuality, and who cites the infamous Romans 1:26-27 as proof, I almost always offer this rejoinder: “What do you make of the vocative at the beginning of Romans 2?”

The question is admittedly pretentious on my part but I’ve found it effective, because those often most eager to wield the Bible as an authoritative weapon are also often those who have read it only in translation, and not very closely at that.

But it’s not an idle question.

Anyone who has engaged the issue of sexuality and the Bible has at some point contended with Romans 1:26-27: “For this reason God gave them up to degrading passions. Their women exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural, and in the same way also the men, giving up natural intercourse with women, were consumed with passion for one another. Men committed shameless acts with men and received in their own persons the due penalty for their error.” (NRSV)

Sounds pretty bad, and indeed, so does the entire last half of the first chapter of Romans. Who, broadly, is being described here? Most agree it’s the Gentiles, and most agree that what is being represented here is boilerplate, Hellenistic Jewish material that attacks the Gentiles. But the condemnatory nature of the verses from 1:18-32 also fits awkwardly, if at all, with the spirit of the rest of the epistle, which goes from talking about the “uprightness of God” in the early verses to suddenly referring to the “anger of God” here, an anger that God uses to “hand over” these people to all manner of horrible behaviors.

But then, they’re Gentiles. They’re rotten, horrible individuals. Did you hear the sorts of things they do? In fact, as pointed out by scholar Calvin Porter, “they” recurs in this section with striking concentration, with repetition of the third-person pronoun αὐτός thirteen times, the reflexive (“themselves”) once, and third-person plural verbs over and over: “No other section of Romans contains such a concentration,” he observes.

What’s even more striking, notes Porter, is what comes next: an abrupt change to the second person in Romans 2:1:

“Therefore you have no excuse, whoever you are, when you judge others; for in passing judgment on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, are doing the very same things.”

Here, then, is the vocative in the Greek, “Oh man,” a grammatical case used for direct address: ὦ ἄνθρωπε. And this takes us to the question I have posed to those who repeat 1:26-27 in condemnation. Who’s the ἄνθρωπος that Paul’s addressing here?

It’s actually a very big question.

Scholarship has been preoccupied often with the content of verses 1:26-27 to the distraction of its context. Scholars such as James Miller and Mark D. Smith have gone back and forth as to whether the behavior described in those verses can be considered “homosexual” from our culture’s standpoint, or whether they refer to something else entirely. But an even more interesting angle surfaced in Roy Bowen Ward’s entry into the fray: “It is still open to question whether these two verses represent Paul’s voice or the voice of a rhetorical spokesperson in Rom 1:18-32, whom the apostle criticizes beginning in Rom 2:1.”

That’s right. Some scholarship of late, of which Porter’s article is the most thorough example, has noted that Romans 1:18-32 does not represent Paul’s view, but the prevailing view of Gentiles among many Jews at the time, which this apostle to the Gentiles feels compelled to refute. Building off of the scholarship of J.C. O’Neill (who calls it “a traditional tract which belongs essentially to the missionary literature of Hellenistic Judaism”) and E.P. Sanders (who explains that “Paul takes over to an unusual degree homiletical material from Diaspora Judaism”), Porter ultimately concludes that “in 2:1-16, as well as through Romans as a whole, Paul, as part of his Gentile mission, challenges, argues against, and refutes both the content of the discourse and the practice of using such discourses. If that is the case then the ideas in Rom. 1.18-32 are not Paul’s. They are ideas which obstruct Paul’s Gentile mission theology and practice.”

Other explanations of what ὦ ἄνθρωπε is doing here are less satisfactory. Some have suggested that Paul is sincerely making these condemnations, stressing here (but only here) God’s anger instead of his kindness (as in 2:4), and then he imagines some onlooker applauding what he’s saying and turns to address him, condemning him for judging but somehow still agreeing with the content of what was just said.

Porter’s argument (which he thoroughly supports with rhetorical models from antiquity) makes much more sense: that the arguments present in the last half of Romans 1 were typical of those made by Hellenistic Jews to distinguish themselves from the Gentiles (thus the repeated use of “they” as noted before), and Paul, as an apostle to the Gentiles, finds this condemnation problematic and thus seeks to refute it, leading up ultimately to his similar conclusion in Romans 14:13, using strikingly similar language to that in 2:1: “Let us therefore no longer pass judgment on one another, but resolve instead never to put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of another.”

Paul goes on to offer advice on healing the rifts between Jew and Gentile, so Porter’s reading is compelling, and certainly the best I’ve seen for answering the question of who’s being addressed in 2:1: “The shift to the direct address, the second person singular, along with the coordinating conjunction, διό, indicates that the reader who agrees with or is responsible for 1.18-32 is now the person addressed.”

Of course, there will be all sorts of arguments apologizing for the words of 2:1 so that one can keep the words of 1:26-27 as a straight-up, unambiguous condemnation, which one can then rely upon to rationalize all manner of discrimination against gays and lesbians. But the flurry of scholarship on this score, not to mention all of that preoccupied with the words of 1:26-27 themselves, should in the very least make it clear that it’s not all that clear.

It’s yet another example of how close study of the Bible — in this case, the function of a single word — raises far more questions than it does answers.

About Don M. Burrows

About Don M. Burrows

Don M. Burrows is a former journalist and current college preparatory school teacher. Don holds a Ph.D. in Classical Studies from the University of Minnesota. A former Christian fundamentalist, Don is now a member of the United Church of Christ and contends most firmly that the Bible cannot be read or explored without appreciating its ancient, historical context. Don lives in Minneapolis with his wife and three young children. Don blogs at Nota Bene and can also be found on Facebook.

Leave a Reply