Let’s briefly take a look at one of the knottiest textual problems in the New Testament: 2 Peter 3:10.

For the purposes of this discussion, we’ll set aside issues of canonicity (hotly-contested) and authorship (not Peter) and simply focus on the text of this single verse.

The NIV renders 3:10 as:

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief. The heavens will disappear with a roar; the elements will be destroyed by fire, and the earth and everything done in it will be laid bare.

For this same text the NASB reads:

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief, in which the heavens will pass away with a roar and the elements will be destroyed with intense heat, and the earth and its works will be burned up.

As you can see, the final verb differs in each translation. Why? Because the NIV’s “laid bare” is a translation of the Greek εὑρεθήσεται, which literally means “will be found,” while the NASB is translating κατακαήσεται, which literally means “will be burned up.” This isn’t a subtle difference: it’s a matter of two completely different words with completely different meanings. So where do those words come from?

Many of our earliest and best Greek manuscripts, including Codex Sinaiticus (א, 4th c.), Codex Vaticanus (B, 4th c.), Codex Mosquensis (Kap, 9th c.) and Codex Porphyrianus (Papr, 9thc.) read “εὑρεθήσεται” — “will be found.”

But another manuscript tradition, which includes Codex Alexandrinus (A 5th c.), 048 (5th c.), 049 (9th c.), 33 (9th c.) and many others, reads “κατακαήσεται,” — “will be burned up.”

But that’s not the end of it: Codex Ephraemi (C, 5th c.) uses yet another verb: “ἀφανισθήσονται” — “will vanish,” the Sahidic Coptic (copsa 3rd/4th c.) and Philoxenian Syriac (syrph, 6th c.) read “οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται” — “will not be found” and Codex Athous Lavrensis (Ψ, 8th/9th c.), the Vulgate (vg, 4th c.) and Pelagius all simply omit the end of the verse.

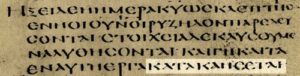

To top it off, our earliest Greek manuscript of 2 Peter 3:10, P72, from the 3rd/4th century, uses εὑρεθήσεται, but adds λυόμενα after it, thus reading “will be found dissolved.”

All of that adds up to the fact that our five earliest Greek manuscripts of this passage offer four different readings: א, B, Kap, Papr, etc. read εὑρεθήσεται. A, 048, 049, 33, etc. read κατακαήσεται. C reads ἀφανισθήσονται, and P72 reads εὑρεθήσεται λυόμενα.

We’ve seen where these variations come from, but the real question is why do we have these differences? It’s because what appears to be the earliest and best reading — εὑρεθήσεται — simply doesn’t make sense. Bruce Metzger, in A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, goes so far as to say: “εὑρεθήσεται, though the oldest of the extant readings, seems to be devoid of meaning in the context.”

Here we have a picture of apocalyptic destruction: the heavens disappear, the elements are destroyed, and the earth is … found? It’s as if you were describing a house fire and said, “It’s a total loss, the fire consumed everything, all my possessions were destroyed, the entire yard was burned to ashes, I couldn’t save anything — but I found my house!” Nonsensical, to say the least!

Scribes copying the Bible realized this issue from very early on and were quick to try and remedy it, hence the reading in P72: “will be found dissolved,” C: “will vanish,” and A: “will be burned up,” all of which make much more sense in the context of this passage. It makes perfect sense to say “My house caught on fire and everything was burned up,” or “My house caught on fire and I found everything destroyed.”

The crux of the issue is this: our earliest extant manuscripts don’t seem to make sense, so later manuscripts changed the text.

But what did the original text actually say?

We have three options available for our understanding:

- A conjectural emendation: substituting words or letters to come up with something that does make sense. This is essentially what scribes did when they started using κατακαήσεται. The problem here is that we’re basically guessing. Scholars have proposed all sorts of creative manipulations of the text that attempt to solve the problem. But without extant manuscript support, they’re just shots in the dark.

- Accept one of the variant readings that does make sense, despite the fact that there aren’t any extant manuscripts that satisfactorily connect them to an original text.

- Accept our best text as is and come up with a different understanding of εὑρεθήσεται — an understanding that does make sense in this context.

Richard Bauckham in his commentary on 2 Peter provides a detailed discussion of all these options and though he is sympathetic to the second choice, he ultimately accepts the third option as the best — or perhaps the least worst.

This is also the choice of virtually all modern translations: accept εὑρεθήσεται as the true text — following in the path the eclectic Greek text first compiled in Westcott and Hort’s The New Testament in the Original Greek — and then provide an English translation that moves εὑρεθήσεται past its primary meaning in order to makes sense of the sentence. This can be seen in the variety of translations of εὑρεθήσεται: “found to deserve judgement” (NLT), “will be laid bare” (NET, NIV), “God will judge” (NIRV), “will be exposed” (CEB, ESV, GW, ESV), “will be disclosed” (HCSB, NRSV).

All these interpretations are confidently put forth in our English translations despite the fact that we have no extant manuscripts in which εὑρεθήσεται clearly carries any of those meanings. To be fair, these translations merely reflect the best scholarship that was available to them. The NA27 chose εὑρεθήσεται as the “best” reading for that verse, though it gave it a D rating, representing its lowest degree of certainty. However, most English Bibles have no way of conveying that uncertainty; at best they include a brief note along the line of the ESV’s: “Greek found; some manuscripts will be burned up.”

However, in 2013 the NA28 was published. This new edition of the Greek New Testament incorporates the text from the second edition of the Editio Critica Maior. The ECM represents the latest scholarly work on the Catholic Epistles using the Institute for New Testament Textual Research‘s (INTF) Coherence-Based Genealogical Method, a technique for evaluating textual decisions that, to my mind at least, is somewhat akin to quantum theory: “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”

And, lo and behold, the scholars at the INTF declared that “οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται” — “will not be found” — is now the best reading for 2 Peter 3:10. They decided that the common reading of “εὑρεθήσεται” was all but incomprehensible, and so chose the most straightforward textual emendation that made sense of the text. The emendation of “οὐχ” — “not” — isn’t complete conjecture since it is present in early Coptic and Syriac manuscripts, but it still borders on a “guess” since we have no early Greek manuscripts that actually reflect this reading.

Why does any of this matter?

First, textual issues such as this pose a serious challenge to notions of Biblical inerrancy. Even if we try to sidestep the issue and claim that inerrancy holds true for only the original autographs, the doctrine of inerrancy is, practically speaking, rendered moot since we don’t have those autographs and, especially in this case, really don’t have a good idea of what the original actually said. Even the best scholarship in the world is unable to determine the original reading of 2 Peter 3:10 with any meaningful degree of certainty and most modern English translations now reflect the exact opposite meaning of the latest edition of the Greek text upon which their translations are based. Faced with this conundrum, one must either admit that we don’t have the very Word of God contained in the pages of the Bible, or else arbitrarily choose a specific version and by reason of blind faith alone declare it to be the inspired, inerrant Word of God. This latter option offers the ease of essentially ignoring textual issues like the one presented above, but is tantamount to sticking your head in the sand.

Second, there are significant theological implications at stake in this verse. The eschatology reflected in 2 Peter, if taken seriously, will affect how we live here and now, how we value the environment and how we view God’s final judgement. Does what we do here on Earth now really matter? Will it all be “burned up?” Will it be subjected to God’s judgement and “exposed” for all to see? Or is this all just apocalyptic balderdash that represents a (possibly Gnostic) worldview that Christians should be wary of?

Finally, as Christians we must be aware of these issue because they affect the text that is at the center of our faith. We must be honest in how we understand the Bible, willing to confront the difficulties head-on and not shirk our call to live for truth. These challenges should serve as a warning lest we become overconfident that we have, in any single translation, version or manuscript, a perfect representation of God’s Word.

Dan Wilkinson

Dan Wilkinson

Dan is the Executive Editor of the Unfundamentalist Christians blog. He is a writer, graphic designer and IT specialist. He lives in Montana, is married and has two cats.

Leave a Reply